[et_pb_section admin_label=”section”]

[et_pb_row admin_label=”row”]

[et_pb_column type=”4_4″][et_pb_text admin_label=”Text”]Educators should take a cue from marketers who’ve been using mental triggers to sell products for decades. Educators can use triggers to activate students’ deeper thinking skills. The process is simple and highly effective. The short article below introduces the tactic and provides a few examples of its impact.

Have you ever noticed that many of America’s most successful television commercials have little to do with the products they’re advertising? Instead, the advertisements seek to evoke responses from a much deeper place within our psyche.

You do realize that those Coke commercials don’t tell us anything about Coke’s capacity to quench our thirst. Instead, the advertisements feature friends sharing happy times, families during the holidays, and traditions. In fact, Coke’s most recent “Share a Coke with…” campaign removes all ambiguity by printing words such as “Friends,” “Family,” and “Tradition,” directly on the bottles. You can even have bottles personalized with names of your choosing.

The objective of such trigger advertisements is to make us associate certain environmental cues with the products. The intended effect is that the next time we gather with family, celebrate a tradition, and so forth, we will bring Coke to make it an event.

Marketers have been using visual triggers like this forever.

Question whether they work: At one time,

bacon and eggs were not united, nor were milk and cookies. Long ago, clever marketers joined these once separate food items to improve sales. Now they are forever linked in society’s food subconscious.

These tactics are both highly viscerally effective and surprisingly simple. A trigger is a mechanism that causes something else to happen. So when advertisers couple their products with a particular environmental cue, they’re betting that the cue will trigger our association with their products and influence buying behavior.

Perhaps most effectively, all of the actions that influence us to buy a company’s products happen beyond our immediate awareness. We don’t make explicit connections between the beach and craving a cold Corona or eating cookies and drinking milk. But this is why industries and companies invest so heavily in research. They know that these associations don’t happen by chance; they are established through sound marketing practices.

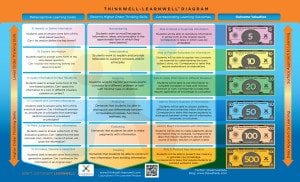

In the same way, educators can use triggers to improve student learning. In 2013, I added the fourth column to the ThinkWell-LearnWell Diagram after reading scientific studies on the brain’s proclivity for

In the same way, educators can use triggers to improve student learning. In 2013, I added the fourth column to the ThinkWell-LearnWell Diagram after reading scientific studies on the brain’s proclivity for

1. converting repeated mental actions into autonomic routines,

2. assigning value to mental actions, and

3. using environmental cues to automatically trigger these stored sequences

For many students, school serves as an environmental cue that triggers lower-level memorization. These students have been conditioned to autonomically prioritize memorization over other cognitive functions. While learners may use a variety of thinking skills throughout their lives, they tend primarily to use memorization during school activities. Educators can strategically use the diagram to help students differentiate and re-value their skills. This process has become a staple in all of my work with students. I’m pleased with the positive responses from learners as they internalize this process and recalibrate their thinking. Additionally, it’s been a delight to see how easily students are nudged toward better thinking.

I’ve also enjoyed hearing feedback from educators who have witnessed similar results. For example, the video below features students from Hickory High School in Hickory, NC, sharing the impact that incorporating metacognitive tools and tactics into their class had on them (the diagram being the primary tool). The video also includes footage from a graduate intern teacher referring to the diagram as part of her metacognitive strategy. (She already had taught her students how to use the diagram earlier in the year.) As the video at the end of this article indicates, the intern’s students improved their scores over the previous year’s class by nearly 20 points and performed 35 points higher than the state average, according to North Carolina’s Department of Public Instruction testing scores.

Angie Ruppard’s developmental math class provides another example of an educator skillfully using the ThinkWell-LearnWell Diagram to actuate deep thinking abilities. While following up to a series of professional development workshops with educators at Caldwell Community and Technical Institute, in Hudson, NC, Mrs. Ruppard, a developmental math instructor, allowed me to sit in on one of her classes. Having integrated the diagram into previous instruction, she asked students to solve problems on the board. Then, as they demonstrated various thinking skills, she handed them a LearnWell Projects’ monetary denomination consistent with the thinking skills they were demonstrating.

It was pretty cool watching this simple tactic transform this classroom of traditional-aged students and adult learners into a competitive group as they were explicitly trying to exhibit the highest level of thinking. Students were cheering each other on. More important than the engaging atmosphere, the students were consciously differentiating their thinking skills and assigning value to the cognitive behaviors in real time. Results: 96% of her students passed the class that I visited and 100% of students in her other developmental math class.

These are just a couple of examples of how the ThinkWell-LearnWell Diagram has triggered deeper thinking within students and greater satisfaction among educators. You too can begin activating students’ deeper thinking. Download a free version of the diagram at the following link: https://thelearnwellprojects.com/tools, or you can purchase the poster-sized version from the store to hang in your classroom or learning center, or even your student’s bedroom.

Advertisers have used mental associations to boost their sales for decades. It’s about time educators use this best practice to accomplish their goals as well. The improved ThinkWell-LearnWell Diagram makes this process much easier.

https://youtu.be/vM144FSQJi0[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column]

[/et_pb_row]

[/et_pb_section]