[et_pb_section fb_built=”1″ _builder_version=”4.21.2″ _module_preset=”default” width=”100%” max_width=”100%” custom_padding=”30px|0px|30px|0px|true|true” global_colors_info=”{}”][et_pb_row _builder_version=”4.21.2″ _module_preset=”default” global_colors_info=”{}”][et_pb_column type=”4_4″ _builder_version=”4.21.2″ _module_preset=”default” global_colors_info=”{}”][et_pb_video src=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f6h19_WKXhY” _builder_version=”4.21.2″ _module_preset=”default” custom_margin=”||5px||false|false” global_colors_info=”{}”][/et_pb_video][et_pb_text _builder_version=”4.21.2″ _module_preset=”default” text_font=”|600|||on||||” text_text_color=”#000000″ text_orientation=”center” global_colors_info=”{}”]

Click on the clip to view the full video on YouTube.

[/et_pb_text][et_pb_text _builder_version=”4.21.2″ _module_preset=”default” text_font=”||||||||” text_text_color=”#333333″ link_font=”|700|||on|||#215921|” link_text_color=”#215921″ global_colors_info=”{}”]

In part 1 of Metacognition Matters, I focused on metacognition and metacognitive knowledge. And we learned about three students whose belief that they aren’t good writers came from very different metacognitive knowledge. If you haven’t read that post, please go back and read it!

[/et_pb_text][et_pb_text _builder_version=”4.21.2″ _module_preset=”default” text_font=”|700|||||||” text_text_color=”#215921″ text_font_size=”20px” custom_margin=”||10px||false|false” global_colors_info=”{}”]WHERE DOES METACOGNITIVE KNOWLEDGE COME FROM?[/et_pb_text][et_pb_text _builder_version=”4.21.2″ _module_preset=”default” global_colors_info=”{}”]Students acquire metacognitive knowledge from three sources: naive and ill‑formed belief systems about learning; judgments and feedback from other people, such as teachers, parents, and peers; and metacognitive experiences.

Metacognitive experiences are emotion‑driven inferences students make based on affective experiences such as fondness, curiosity, and disappointment. Metacognitive experiences can be positive and helpful or negative and destructive. Researchers have discovered metacognitive activity in humans from as early as age three. Rest assured, by the time students become college-age, they have well‑established metacognitive knowledge bases, which can either help or hurt them.

For example, David struggled with school early on in life. However, he improved his performance through hard work and learning new strategies and is now viewed as a good student. The judgments from his teachers in the form of good grades and positive statements from his parents and peers shaped the belief he has of himself as a strong student. Furthermore, he deduced from his early experiences that he could overcome academic struggles through hard work and executing the proper strategies. The accumulation of fond affective feelings infused David with positive metacognitive experiences that manifest as positive metacognitive knowledge. This metacognitive knowledge constantly plays in the background of David’s mind.

Paul, on the other hand, was an excellent student. Throughout his early years, he was told he had an excellent memory. As a result, Paul developed several memory‑based strategies for learning. His parents, teachers, and peers constantly lauded his academic skills, and he deduced from these positive experiences that he was a great student and that learning was easy. He entered college feeling confident about himself as a learner.

Early on, however, Paul struggled for the first time. He couldn’t understand why his grades wouldn’t improve despite studying more than ever. The accumulation of negative judgments about his performance (in the form of poor grades) drowned out his optimistic metacognitive script and triggered Paul to question his academic abilities. For the first time, he began to believe that perhaps he wasn’t a strong student and wasn’t college material.

It’s important to keep in mind that both Paul’s and David’s metacognitive activities occur on their subconscious levels. Neither student would connect their academic situation to their metacognitive knowledge. More than likely, they would strongly attribute it to other factors. This leads us to metacognitive awareness.[/et_pb_text][et_pb_text _builder_version=”4.21.2″ _module_preset=”default” text_font=”|700|||||||” text_text_color=”#215921″ text_font_size=”20px” custom_margin=”||10px||false|false” locked=”off” global_colors_info=”{}”]HOW DO WE HELP STUDENTS DEVELOP METACOGNITIVE AWARENESS?[/et_pb_text][et_pb_text _builder_version=”4.21.2″ _module_preset=”default” link_font=”|700|||on|||#215921|” link_text_color=”#215921″ link_font_size=”13px” global_colors_info=”{}”]

Metacognitive awareness is students’ mindfulness of the interplay between their metacognitive activity and cognitive processes and how these factors influence their thinking and feeling during academic work. Students must awaken to their metacognitive activity before they can develop metacognitive skills and ultimately control their thinking and feelings while doing academic work. Paul’s feelings of frustration and despair over his continued underperformance were rooted in negative metacognitive experiences. His feelings were raw and real, and they fueled his negative view of himself. The onslaught of metacognitive negativity switched Paul’s optimism to negativism.

Metacognitive assistance (part of what we do at The LearnWell Projects) involves making metacognitive processes explicit to students, providing a language to articulate these experiences, and equipping students with tools to improve their metacognitive skills. Making students aware of the metacognitive activity that is directing their thinking and performance is a vital first step for educators. We want to move students from awareness to control.

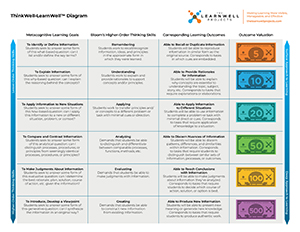

DOWNLOAD THE THINKWELL-LEARNWELL™ DIAGRAM HERE.

For example, in my Transforming Good Students into Great Learners Workshop, which targets hardworking but low‑performing students, I show students and educators how to use the ThinkWell‑LearnWell™ Diagram to optimize students’ thinking. The sequence of improvement goes like this:

First, I use the diagram to help students see the relationships among their metacognitive functioning, thinking skills, and outcomes. This increases their metacognitive knowledge about their cognition.

Then I show them the disparity between their current standard of thinking and outcomes and the modes of thinking needed to produce the kinds of outcomes their professors require. This increases their awareness.

Finally, I help them develop new strategic‑thinking skills. This increases their metacognitive abilities.

By the time the session concludes, they are transformed from unproductive students to productive learners. They learn valuable skills and a process that elevates their performance beyond their previous performance ceilings. They also gain new, helpful metacognitive knowledge about academic tasks and how they can produce better academic work.

The positive metacognitive experiences they accumulate during the workshop overpower their previous negative metacognitive experiences. And they leave the workshop with transferable skills that they can use across academic disciplines and other areas of life. It’s fascinating to witness how quickly students go through the stages of metacognitive awareness and begin controlling their production of academic work.

[/et_pb_text][et_pb_text _builder_version=”4.21.2″ _module_preset=”default” text_font=”|700|||||||” text_text_color=”#215921″ text_font_size=”20px” custom_margin=”||||false|false” locked=”off” global_colors_info=”{}”]AWARENESS IS THE FIRST STEP TOWARD DEVELOPING NEW SKILLS.[/et_pb_text][et_pb_text _builder_version=”4.21.2″ _module_preset=”default” locked=”off” global_colors_info=”{}”]Metacognitive skill is the fourth component of metacognition. Metacognitive skills are students’ ability to monitor, guide, direct, and control their learning and to strategically solve problems regarding their learning as they arise. Students typically exhibit metacognitive skills at one of three academic work phases: preparation at the start of an activity; during the activity, to monitor their execution; or after an activity as a reflective or evaluative tactic.

Metacognitive skills cannot be directly assessed. They must be inferred from their behavioral consequences. For example, if a student decides to reread a passage of text for greater comprehension, then we can infer that the student’s metacognitive evaluation skills judged her reading as inadequate, and as a consequence, she activated a cognitive strategy of rereading in an attempt to increase her comprehension. This example shows the constant interplay between metacognitive skills and cognitive functioning.[/et_pb_text][et_pb_text _builder_version=”4.21.2″ _module_preset=”default” text_font=”|700|||||||” text_text_color=”#215921″ text_font_size=”20px” custom_margin=”||||false|false” locked=”off” global_colors_info=”{}”]PARTING THOUGHTS[/et_pb_text][et_pb_text _builder_version=”4.21.2″ _module_preset=”default” locked=”off” global_colors_info=”{}”]

Now that I’ve shared how valuable metacognition is to students, I’ll conclude by sharing some examples of how metacognitive training and instruction have helped solve real‑life problems at my clients’ institutions:

- Quick turnaround: a three-pronged metacognitive approach at Florida Polytechnic University improved D, F, W rates in gateway courses by 19 percent from August 2021 to December 2022. Faculty and students report stronger alliances and an improved interest and aptitude in more complex academic work.

- Sharp increase: the metacognitive program at Wesleyan College produced a 35 percent increase (from 22 to 57 percent) in academic probationary students who moved into solid academic standing between spring 2019 and fall 2020. In addition, faculty and students reported greater satisfaction with the learning environment.

- Real student-athlete success: a student-athlete focused program at the University of Cumberlands increased the football team’s GPA from 2.1 to 3.1 in one semester. The athletics program maintained over a 3.0 GPA.

- 1-Hour of Power: after participating in an online metacognitive training program, learning center leaders at Mount Mary College reported 35 to 40 percent increases in students’ grades.

- Program overhaul: the University of California San Diego’s Triton Achievement Hub developed a peer-based metacognitive assistance program that improved student learning and performance across several support platforms.

If you would like to explore ways your program or institution can use metacognition to achieve your goals, then I’d love to share my expertise with you. Contact me by email at learning@thelearnwellprojects.com.

[/et_pb_text][et_pb_image src=”https://thelearnwellprojects.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/metacognition-mosaic-PDF-preview.jpg” title_text=”metacognition mosaic – PDF preview” _builder_version=”4.21.2″ _module_preset=”default” global_colors_info=”{}”][/et_pb_image][et_pb_text _builder_version=”4.21.2″ _module_preset=”default” locked=”off” global_colors_info=”{}”]

Get the whole article and the Three Levels of Metacognition poster in PDF form by leaving a thoughtful response in the “comments” section.

See you in the comments!

Bibliography

Batha, K., Carroll, M. (2007). Metacognitive training aids decision making. Australian Journal of Psychology, 59(2), pp. 64–69.

Coutinho, S.A., Neuman, G. (2008). A model of metacognition, achievement goal orientation, learning style and self‑efficacy. Learning Environments Research, 11(2).

Eccles, J. S., Wigfield, A., & Schiefele, U. (1998). Motivation to succeed. In W. Damon &

N. Eisenberg (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology: Social, emotional, and personality development (p. 1017–1095). John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Flavell, J.H. (1979). Metacognition and cognitive monitoring: A new area of cognitive‑ development inquiry. American Psychologist, 24(10), pp. 906–911.

Hall, C.W., & Webster, R.E. (2008). Metacognitive and affective factors of college students with and without learning disabilities. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 21(1),

pp. 32–41.

Hall, N.C., Hladkyj, S., Perry, R.P., & Ruthig, J.C. (2004). The role of attributional retraining and elaborative learning in college students’ academic development. The Journal of Social Psychology, 144(6), pp. 591–612.

Halpern, D.F. (1998). Teaching critical thinking across domains: dispositions, skills, structure training, and metacognitive monitoring.

American Psychologist, 53(4), pp. 449–455.

Hargrave, A., Ryan, Nietfeld, L., John (2015). Learning, Instruction, Cognition. The Journal of Experimental Education, 83(3), 291–318

Hennessey, M.G. (1999). Probing the dimensions of metacognition: Implications for conceptual change teaching‑learning. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the National Association for Research in Science Teaching, Boston, MA.

Kelemen, W.L. (2000). Metamemory cues and monitoring accuracy: Judging what you know and what you will now. Journal of Educational Psychology, 98(4) pp. 800–810.

Kuhn, D., & Dean, D. (2004). A bridge between cognitive psychology and educational practice. Theory into Practice, 43(4), pp. 268– 273.

Mango, C. (2009). The role of metacognitive skills in developing critical thinking. Metacognition Learning, 5, pp. 137–156.

Mussweiler, T. (2003). Comparison processes in social judgment: mechanisms and consequences. Psychological Review, 110(3),

pp. 427.

Schraw, G., & Dennison, R. S. (1994). Assessing metacognitive awareness. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 19, pp. 460–475.

Scheibe, K.K., Mennecke, B.M., & Luse, A.A. (2007). The role of effective modeling in the development of self‑efficacy: the case of the transparent engine. Decision Science Journal of Innovative Education, 5(1), pp. 21–42

Taylor, S. (1999). Better learning through better thinking: Developing students’ metacognitive abilities. Journal of College Reading and Learning, 34–45.

Young, A., & Fry, J. (2012). Metacognitive awareness and academic achievement in college students. Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 8(2), pp. 1–10.

Watson, G., & Glaser, E. M. (1964). Watson-Glaser critical thinking appraisal manual. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World.

Whitebread, D., Coltman, P., Pino‑Pasternak, D., Sangster, C., Grau, V., Bingham, S., Almeqdad, Q., & Demetriou, D. (2009). The development of two observational tools for assessing metacognition and self‑regulated learning in young children. Metacognition and Learning, 4, 63–85.

Zohar, A., & Dori, J. (2011). Metacognition in Science Education: Trends in Current Research. Springer Publishing.

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][/et_pb_section]