[et_pb_section admin_label=”section”]

[et_pb_row admin_label=”row”]

[et_pb_column type=”4_4″][et_pb_text admin_label=”Text”]

First, An Example of The Experience Economy

If a picture is worth a thousand words, then how valuable is an experience? As the nation is locked in a heated debate about the cost of higher education, educators must realize that the real issue at hand is value. While cost may be the most widely used construct to discuss education’s rising price tag, the question of value is really at the heart of the matter. Price, cost and value are often conflated as if they mean the same thing, but they are very different. Cost is simply a numerical assignment for the total resources it takes to produce a product or service. Price is determined by the amount people are willing to pay for a good or service. Value is largely determined by the real or perceived benefit a product or service will deliver. So the real question is how much is higher education worth to an individual, a family, a community, a nation? Addressing this question will get rather lengthy, so I will focus this article on the learning assistance profession. However, know that the concepts that underlie the experience economy are working throughout higher education and beyond.

If a picture is worth a thousand words, then how valuable is an experience? As the nation is locked in a heated debate about the cost of higher education, educators must realize that the real issue at hand is value. While cost may be the most widely used construct to discuss education’s rising price tag, the question of value is really at the heart of the matter. Price, cost and value are often conflated as if they mean the same thing, but they are very different. Cost is simply a numerical assignment for the total resources it takes to produce a product or service. Price is determined by the amount people are willing to pay for a good or service. Value is largely determined by the real or perceived benefit a product or service will deliver. So the real question is how much is higher education worth to an individual, a family, a community, a nation? Addressing this question will get rather lengthy, so I will focus this article on the learning assistance profession. However, know that the concepts that underlie the experience economy are working throughout higher education and beyond.

Recently, I was honored to serve as keynote speaker of the 2015 Association for the Tutoring Profession/Association of Colleges for Tutoring and Learning Assistance ATP/ACTLA joint conference in San Francisco, CA. After my keynote address I decided to visit Pier 39, the popular tourist attraction. A high-end establishment called Forbes Island Restaurant caught my attention. It was advertised as the world’s only man-made floating restaurant. The funny thing is that the restaurant was only about a 100 yards from the land. The process of boarding patrons onto the small boat that carried them to the eatery took longer than the two-minute leisurely commute to the “island.” Dining at Forbes Island is more expensive than the surrounding restaurants. I happened to catch a family leaving the small restaurant and asked them what they thought of the establishment. They said the food was great, the service was personalized, but the experience was awesome. One of them said it was, “definitely worth the price.” “What was so great about the experience?” I asked. One of the members in the party quickly replied, “It’s on an island!” This exchange provides a window into the experience economy. This family valued the experience of eating on an island so much that they were willing to pay a premium. What did the family get for that price? Was the food better than the other restaurants? Maybe. Was the service better than its competitors? Doubt it. One thing was certain: more than selling great food, Forbes Island was selling an experience! The product of food and the services provided to patrons, from taking patrons on a boat to serving them while they eat, are mere props and stages used in creating memorable experiences.

Recently, I was honored to serve as keynote speaker of the 2015 Association for the Tutoring Profession/Association of Colleges for Tutoring and Learning Assistance ATP/ACTLA joint conference in San Francisco, CA. After my keynote address I decided to visit Pier 39, the popular tourist attraction. A high-end establishment called Forbes Island Restaurant caught my attention. It was advertised as the world’s only man-made floating restaurant. The funny thing is that the restaurant was only about a 100 yards from the land. The process of boarding patrons onto the small boat that carried them to the eatery took longer than the two-minute leisurely commute to the “island.” Dining at Forbes Island is more expensive than the surrounding restaurants. I happened to catch a family leaving the small restaurant and asked them what they thought of the establishment. They said the food was great, the service was personalized, but the experience was awesome. One of them said it was, “definitely worth the price.” “What was so great about the experience?” I asked. One of the members in the party quickly replied, “It’s on an island!” This exchange provides a window into the experience economy. This family valued the experience of eating on an island so much that they were willing to pay a premium. What did the family get for that price? Was the food better than the other restaurants? Maybe. Was the service better than its competitors? Doubt it. One thing was certain: more than selling great food, Forbes Island was selling an experience! The product of food and the services provided to patrons, from taking patrons on a boat to serving them while they eat, are mere props and stages used in creating memorable experiences.

Patrons don’t only leave Forbes Island with a momentary full stomach; they received a priceless memory that can be shared forever. Search Forbes Island on the Internet and you’ll encounter more quotes about the experience than the food. Listen up my fellow learning assistance professionals because we must take an economic cue from Forbes Island, and numerous other businesses and schools, and fully embraced the experience economy. Our personal and professional success may depend on it. We may not be ready to fully acknowledge it, but the learning assistance profession is rapidly losing ground. This state of affairs is not because institutions don’t realize the serious deficiency of skills among their students. They do. But rather than strengthening learning assistance programs, schools are reducing funding and cutting personnel. Hmm, follow me on this: students need out-of-class support, yet institutions won’t invest in those who provide that support. How are we to make sense of this paradoxical trend? The question is best answered by understanding that higher education is transitioning from a service-based economy to an experience economy. In a service economy, services are the primary determinants of value. This means that both the number and quality of services provided dictate one’s worth. In the experience economy, services aren’t as valuable. Experiences are the means of exchange. An experience transpires when we use “services as the stage, and goods as props, to engage individual customers in a way that creates a memorable event” (Pine & James, 1998) (Pine & Gilmore, 2011). This is Forbes Island Restaurant’s business model. For learning assistance professionals, this involves combining the various services we render under one or more broad themes. Then we must create events for students, and other stakeholders, to experience the essence of our theme.

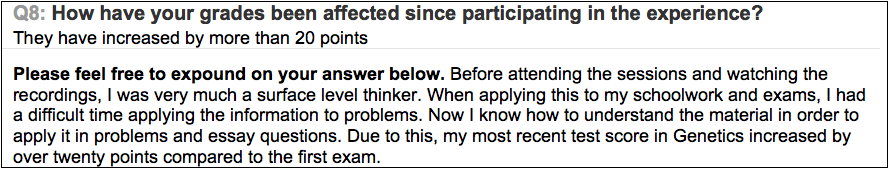

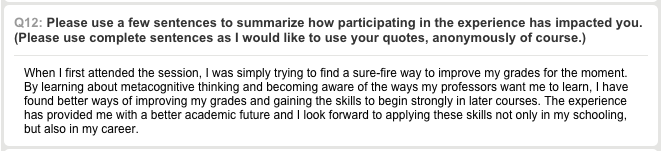

In 2008, I sought to change the support services model at Lenoir-Rhyne University from a service center to an experience-based offering. Like many academic support centers, I’d become accustomed to providing a variety of academic services, such as tutoring, group academic workshops, and personal academic counseling sessions. At the end of each semester, I’d run various reports to show that we were indeed providing useful services. While these activities were effective, I wanted to make a greater impact. I began shifting away from the traditional posture of “providing academic assistance” to embracing the experience economy. The Transforming Good Students into Great Learners experience is one example of how I converted a valuable service into a life-changing experience. The event consolidated and intensified key components of workshops that had been conducted in isolation into a four-hour powerful learning experience. (The experience consists of four one-hour segments spread over four weeks.) As the title suggests, the event transforms “good” students — those whose hard work doesn’t consistently produce great results — into highly productive learners. Participants typically experience about a 20-point increase in test performance. It has led to numerous comments like these:

The line between a service and an experience is thin. However, it is a distinction with an important difference. For a service to become an experience it must evoke strong emotion, be customized and personalized. For example, consider the difference between teaching and educating. Teaching requires delivering information in an organized manner. Most efforts to improve teaching focus on pedagogy, the mechanics of teaching. Sound instructional practices are useful, but they won’t inherently transform the service of teaching into an experience. Educating someone, on the other hand, is accomplished through experiences. Those who work in academic coaching and tutoring programs provide important services to students, but imagine if your services included an ongoing profile of the growth students experienced while involved in your programs. If you don’t already do this, imagine the value that would be conferred upon you and your programs if students who received tutoring or were coached not only learned the content, but they learned how they learn. I don’t mean simply knowing their learning style. But what if students learned how to progress from knowing little to nothing about a domain, which is the place most students begin a class, to systematically producing meaningful outcomes?

What if students knew how to deconstruct their interactions during universal learning tasks such as note taking, studying and reading? More importantly, what if they could reconstitute these tasks in more effective ways when they are deemed ineffective? What if we delivered students personalized profiles that showed them that the skills they gained through our programs have not only helped improve their academic performance, but that they have honed invaluable mental skills that will help them progress in their professional and personal lives. I believe the learning assistance profession holds the key to higher education delivering its next and perhaps highest level of economic value. While the professor-student relationship will always be central to the educational process, institutions must begin placing a higher value on learning assistance services. But learning assistance professionals must step up and move boldly into the experience economy. If you desire to embrace the new experience economy, then seek methods to convert the services you offer into experiences. Below are a few guidelines to consider as you make the shift.

- Create beneficiaries, not participants – Participants are created when students partake of our services. Participants become beneficiaries when they extract personal enduring value from what we do. Our program typically creates indelible memories, the achievement of which requires experiences!

- Commemorative Artifacts – People want mementos to remember experiences. I’ve worked with students to generate “tricked out” before and after videos of the experiences. I want students to have tangible evidence of the transformation they underwent. Click the following link to view this clip: http://bit.ly/1F0EWO1.

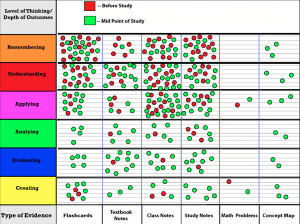

- Personalized Data – Learning about self is key to the experience economy. Each student received a plot chart that showcases their transformation in thinking and learning. This personal memento is the learning equivalent of a before and after picture.

If learning center professionals are willing to embrace the experience economy, then perhaps we can advance the profession and our institutions. Download the abridged version of this article in the National College Learning Center Association’s (NCLCA) Spring Newsletter at the following link: http://nclca.org/newsletters/spring_2015.pdf.

References

- Pine, J. B., & Gilmore, J. H. (2011). The Experience Economy, Updated Edition. Boston, MA, USA: Harvard Business Publishing.

- Pine, J. B., & James, G. H. (1998, July-August N/A). Welcome to the Experience Economy. Retrieved March 30, 2015, from Harvard Business Review: https://hbr.org/1998/07/welcome-to-the-experience-economy

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column]

[/et_pb_row]

[/et_pb_section]