The Silent Struggles Behind the College Transition

Starting college is an exciting journey, full of promise and potential. For both educators and students, the first few weeks are typically filled with anticipation of new academic experiences and challenges. However, this period is also one of the most fragile. Subtle academic and psychological challenges often emerge, and if left unaddressed, they can quickly escalate into serious problems that affect not only students, but entire institutions.

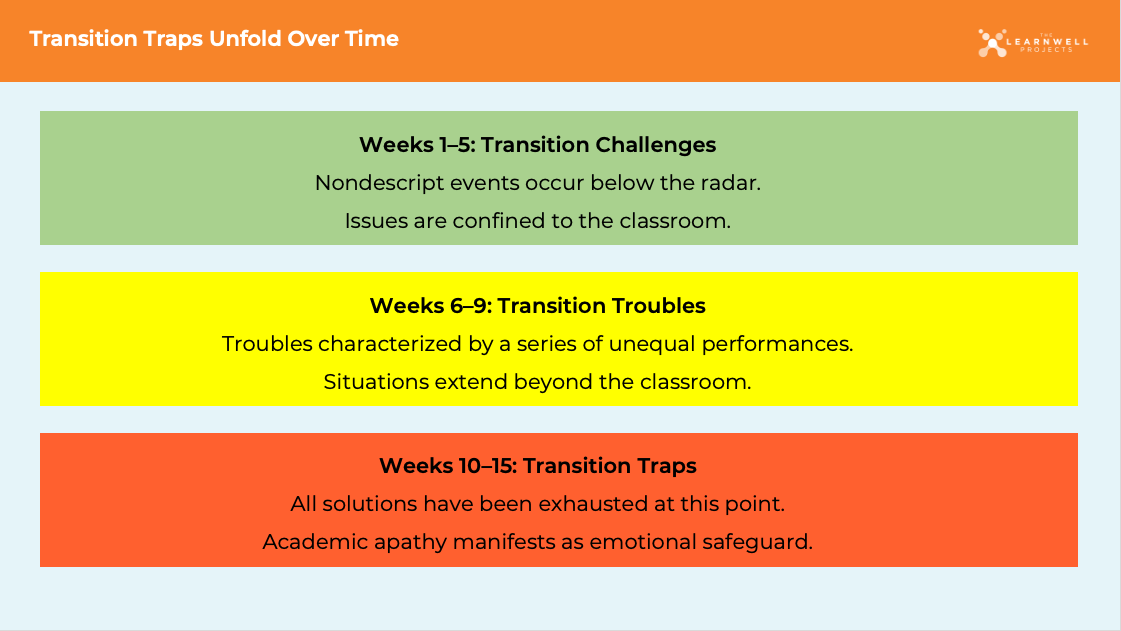

Stage 1: Transition Challenges (Weeks 1–5)

In the first five weeks of college, students often face what I call “transition challenges.” These aren’t dramatic breakdowns, but rather small, hard-to-detect struggles that can silently derail academic momentum.

You might notice:

- Students falling behind on reading and coursework

- Infrequent class participation

- Difficulty connecting ideas throughout a course

During this early stage, students often rely on instructional cues that worked in high school but don’t in college. For example, they may highlight information that instructors repeat, or they over-rely on information presented in PowerPoint slides or notes. Trained observers are needed during this early phase because students typically don’t know that they are already in hot water (and that things will get hotter quickly).

As one student reflected:

When I started college, I did more work than I ever did in high school. When I didn’t understand things in class, I thought my professor would help us make sense of everything before the tests. I didn’t even know I was struggling when I definitely was.” —Adriene, University of California San Diego (UCSD)

Stage 2: Transition Troubles (Weeks 6–9)

If unaddressed, those early challenges evolve into more visible and disruptive “transition troubles.” This is the critical midpoint of the semester, when:

- Performance discrepancies become apparent: students ace quizzes but fail exams.

- Study efforts yield diminishing returns: more time spent studying doesn’t proportionally improve performance.

- Support systems lose effectiveness: tutoring, SI and coaching don’t seem to work, and may make students more dependent on support rather than putting them on a path for independent learning.

Mixed signals about their preparedness cause confusion. Frustration grows. Without effective strategies to adjust, students may spiral.

Seeking help can feel like admitting failure, which makes some students avoid or reject it even when it’s offered. That’s why I often encourage institutions to implement my Peer Learning Strategist model—a proactive approach that normalizes academic support by shifting the narrative from “needing help” to exercising strategy.

I never realized how my study methods were at odds with what my professors expected of me. But working with a Peer Learning Strategist, I learned how to align my thinking with course. I ended up studying less, but making better grades. —Kristina, Denision University

Stage 3: Transition Traps (Weeks 10–15)

By the final third of the semester, unresolved challenges and mounting troubles often solidify into “transition traps.” These traps are not just academic; they’re psychological, emotional, and relational. They represent the point where students stop trying to fix the problem and begin emotionally detaching from the learning process.

You’ll likely see:

-

Apathy and disengagement: Students stop attending class, miss deadlines, or submit work without effort.

-

Emotional volatility: Feelings of frustration, anxiety, or resentment become more visible in interactions with peers, faculty, or support staff.

-

Conflict escalation: Disputes with instructors, negative course evaluations, or even public protests may emerge.

What looks like laziness is often despair. By this stage, students feel they’ve exhausted their strategies. They feel as though the whole system has failed them.

These behaviors aren’t the result of students giving up too easily; they’re the human toll of misapplied effort and ineffective solutions. Many institutions lack the academic infrastructure to help students recover mid-semester. Without the right interventions, transition traps harden students’ belief that they cannot succeed, and they act accordingly. Some express their feelings through outrage, while others suffer through silence, sabotage, or disengagement.

And these traps are contagious. They erode teacher-student trust, undermine peer relationships, and damage institutional credibility. The longer they persist, the harder they are to reverse.

These lessons improved our student retention. Students were citing personal and financial reasons for leaving in their exit interviews. But we all discovered that students felt powerless to improve their acaemic performance. When their grades improved, so did our retention. — Tom Fish, Director of Retention, University of the Cumberlands

Institutional Fallout

While transition traps affect students directly, they indirectly impact the entire institution by making everyone less effective and angrier. What begins as a personal struggle becomes a systemic issue:

- Faculty receive more complaints.

- Academic alert systems trigger.

- Student dissatisfaction rises.

- Escalations occur—sometimes leading to public protests or social media backlash.

Case in point: While consulting with Florida Polytechnic Univeristy in spring 2021, I sat in a student focus group in which participants had organized a public social media campaign against institutional leaders. Faculty believed that students were lazy. Students believed faculty were intentionally trying to trick them. Instead, they were ensnared in transition traps.

The institution had failed to address the root problem: transition traps. Students had exhausted their coping methods and were turning their anger outward.

The story has a remarkable happy ending, which you can read here: The Florida Poly Project.

The Missed Opportunity

The most unfortunate part? Most issues stemming from transition traps are preventable.

With timely interventions—especially between Weeks 1–5—educators and support staff can redirect students before their struggles escalate. Institutions can improve student outcomes, reduce friction, and foster healthier learning environments.

Takeaway Assessments

Use these prompts to assess whether transition traps are affecting your environment:

For Students

| Do you perform well on homework and quizzes but poorly on exams? | That doesn’t make sense, right? In high school, doing well on homework and quizzes usually meant you were on track for success on tests and projects. But in college, this same pattern may signal superficial learning rather than deep understanding. |

| Are your study sessions long but unproductive? | College students shouldn’t focus on “studying” as a time-based activity. Studying is often measured in hours: “I studied so long for this test.” But in reality, no one cares how long you study—only what you learn. I teach my Peer Learning Strategists to set clear conceptual goals that help them study less while learning more. You might be working harder, not smarter. |

| Is tutoring, SI or coaching making you more dependent? | Academic support should unlock your latent learning potential, not make you reliant on others. If you continually need support to keep up, you may be stuck in a transition trap. |

You definitely want to check out the Essential Skills playlist at the end of this post.

For Educators (Including Teaching and Learning Assistants)

| Are students struggling with higher-order assessments? | I distinguish between microlabor (task-based thinking) and macrolabor (conceptual and strategic thinking). Students arrive at college highly trained in microlabor but often underprepared for the macrolabor demands of college-level work. |

| Do students request test guides or maps? | When students are learning effectively, they begin to naturally and accurately anticipate what will be on assessments because they’ve internalized the course’s cognitive framework. Watch the video included with this post. |

| Are students unpleasantly surprised by low midterm grades? | This is a red flag that indicates the need for mid-semester recalibration—both in learning strategies and instructional delivery. |

| Do support services seem less effective over time? | Effective academic support should build independence. If students don’t improve at completing academic work outside of class, it may be time to reassess the learning infrastructure itself. |

Here’s a “Microlabor vs. Macrolabor ” video.

For Parents

| Does your student say they’re working hard but still falling behind? | This often means they’re stuck in a cycle of unproductive effort—working long hours without gaining deep understanding. They need to learn how to align effort with outcomes. |

| Is your student frustrated despite using tutoring or academic support? | Most colleges push students into tutoring, writing or math assistance out of tradition. However, these resources are much more effecitive if students know how to think strategically about learning. |

| Has your student’s confidence or motivation dropped? | A shift in mood or motivation often signals a transition trap. Reassure them that struggle is part of the process, and let them know you know of at least one resource who has helped thousands of students transform Ds and Fs into As! Their frustration and pain is evidence that they are better than their grades suggest — and they know it! They have to learn how to stop being students and start being learners. |

Watch this playlist on The 5 Essential Academic Work Skills students need to succeed. It will make everything make sense!

Stay Sharp, Stay Ahead

Want to lead with clarity and teach with precision?

Follow Leonard Geddes and The LearnWell Projects on your favorite social platform. You’ll gain access to:

- Free tools and resources

- Field-tested insights on student thinking and learning

- Weekly strategies to help you transform challenges into breakthroughs

Because the earlier we catch transition traps, the better everyone performs.

📚 Sources & Further Reading

- Tinto, V. (1993). Leaving College: Rethinking the Causes and Cures of Student Attrition.

- Kuh, G. D. (2008). High-Impact Educational Practices. AAC&U.

- Conley, D. T. (2007). Redefining College Readiness. Educational Policy Improvement Center.

- Geddes, L. (2023). How to Successfully Transition Students into College: From Traps to Triumph

- Geddes, L. (2023). Differentiating Thinking Skills. YouTube Video

#Transitiontraps #HigherEd #StudentSuccess #AcademicSupport #CollegeTransition #TheLearnWellProjects #LeonardGeddes #CognitiveLoad #Macrolabor #Collegeparents

10 comments

Mary Brigham

Your timing with this article was perfect! I appreciate having the questions to ask as students work on figuring out what isn’t working for them… Thank you!

Rhea Swinson Fitzpatrick

Important work here! While students transitioning into new academic environments is not new, what I find “new” is faculty/administrators lack of engagement with the process. I think with all the changes education has gone thru in the past few years, educators are tired and many lack the enthusiasm needed to welcome our new incoming students. I appreciate the questions your article has for both students and educators.

Tracy Darr

One thing that I constantly try to remind myself and other educators, when these kinds of discussions arise, is that students who arrive at college are NOT college students. They are new participants learning to BE college students. I used to keep the same in mind for K-12 educating. When my high school freshmen arrived, I had to remember that they were really 8th graders showing up with the hopes of becoming successful high school students.

We are aware, and even mark, each benchmark in a child’s first few years of life; however, we are all moving in the direction of growth (hopefully) and need benchmarks to help us know when we have arrived.

Leonard Geddes

Great perspective Tracy. One phrase I try to keep in mind is from a colleague who was very successful with first-year students. At the start of each academic year, he say, “Ah, the college freshman, four year removed from middle school and four years removed from adulthood.”

Lynn Dornink

Thank you for providing concrete questions to identify struggling students and specific suggestions for addressing each issue. Working with numerous struggling student sometimes overwhelms me and it’s hard to know where to start!

Leonard Geddes

Hi Lynn,

Thanks for your comment. I’ll send the PDF article over to you. Please share how your students respond to the questions.

Mary Drzycimski-Finn

When reading this article, I immediately thought of a faculty member who was complaining just today about students who seem apathetic and who are not taking advantage of tutoring resources.

Leonard Geddes

Hi Mary,

Thanks for your comment. I’ll send the PDF article over to you. It should bring clarity and help faculty and students work together to end the semester on a high note!

Karen Parrish Baker, Ph.D.

Quite inciteful.

Linda Anderson

This article is very informative and on point.