Updated: August 2025

It’s 2025, and the college landscape is facing greater challenges than at any time in recent history. Amidst shrinking enrollments, federal scrutiny and public skepticism, higher education finds itself in a fight for relevance and resilience. Across the country, provosts, presidents, faculty and learning center leaders are asking the same urgent questions: How do we improve outcomes? How do we build a stronger academic culture? And how do we achieve healthy enrollments?

There is a foolproof answer to these questions: empowering your “good” students — a population that is likely being underserved. This article helps you identify your good students. It shows the valuable institutional outcomes that flow from assisting these students, and it provides five essential lessons that you can immediately use to turn good students into great learners.

This article replaces my original 2013 post, Why Good Students Do ‘Bad’ in College. That piece struck a nerve with educators, students, and parents across North America. It resonated because it explained a dilemma many had witnessed but few had been able to name: why so many high-performing high school students flounder in college.

What I’ve heard most from the hundreds of comments and conversations since that article was published is this: people recognize the problem — often because they’ve lived it. Whether they were the student, the teacher, or the parent, the story felt familiar. Students who once thrived in the classroom suddenly found themselves confused, overwhelmed, and falling behind. And they had no idea why.

Over the past decade, I’ve worked with colleges and universities to address this issue head-on. We’ve implemented strategies that have helped students approach academic work differently — not just working harder, but learning how to learn at a higher level. The outcomes speak for themselves:

- stronger academic performance across student populations,

- more impactful teaching,

- and a shift in student support from reactive triage to intentional transformation.

Institutions that have embraced this approach have seen dramatic drops in DFW rates, improved retention, and better student progression to upper-level coursework and graduation. They are experiencing something they didn’t know was possible: enrollment health!

Still, the work is far from done. Despite growing awareness, good students continue to be the most underserved group on campus — and yet, they remain our greatest untapped resource for student success and culture change.

So, allow me to reintroduce you to your good students!

Who Are “Good Students”?

Good students are the studious individuals at our institutions. They’re the ones who consistently show up to class, take notes, participate in class, and try hard. They are motivated and hardworking — often the quiet engines of your academic community. Good students are not always your highest performers. (But they can — and should – be.)

But here’s the challenge: Studiousness, while admirable, is not enough. Working hard, but in the wrong direction, still produces bad outcomes.

Good students operate on a flawed mental model of academic work. They unconsciously use the same model that is based on the same acts of studiousness that got them through high school. These habits — reviewing notes, attending class, asking questions — are familiar and comforting. But in college, academic work demands more than effort. They need a new mental model for academic work. One that activates different cognitive skills, unlocks deeper learning strategies, and shifts students from doing schoolwork to doing meaningful academic thinking.

As Marshall Goldsmith might say, “What got you here won’t get you there.” In fact, if he hadn’t already used that title, I might’ve named my book The Skills That Get Students into College Won’t Get Them Through College.

As Marshall Goldsmith might say, “What got you here won’t get you there.” In fact, if he hadn’t already used that title, I might’ve named my book The Skills That Get Students into College Won’t Get Them Through College.

Instead, after working with schools to help them identify and develop their good students into superb learners, I titled my breakthrough book: How to Successfully Transition Students into College: From Traps to Triumph.

Because that’s what this work is really about: helping new college entrants transform from students into learners. To do that, we must show them the difference between the work that got them here (into college) and the work that will get them there — a rewarding education, marketable employment skills, an effective thinker, or wherever else there may be.

When I work with schools, I always start with high school because when good students perform poorly in college, we blame their high schools for not properly preparing them. We do this because we wrongly assume that the off-ramp of high school leads directly to the on-ramp of college. The ramps are close to each other, but far too many students fall in the gap.

So, let’s quickly go back to high school.

High School is Working, But Not How You Think

Did You Know This? By the time students enter college, they’ve already invested more than 16,000 hours in academic work. That’s the equivalent of eight years of full-time employment.

Did You Know This? By the time students enter college, they’ve already invested more than 16,000 hours in academic work. That’s the equivalent of eight years of full-time employment.

This pre-college investment should prepare them for college-level success. And yet, year after year, institutions report high rates of underperformance, burnout, and attrition among first-year students — even among those who arrived with stronger GPAs and more impressive transcripts.

Is this just grade inflation? Maybe not.

In fact, Harvard researchers Jal Mehta and Sarah Fine studied some of the most highly acclaimed public high schools across the country. Their goal was to compile all the rich academic work and learning that was going on in these schools into a book on deep learning at the high school level. However, after six years of studying these schools, they changed the title of their book to In Search of Deeper Learning because they reportedly never found students engaging in the quality of cognitive work that they would have to do in college.

What did they find? They found lots of studiousness. Attentive students. Engaged Students. Students who knew how to navigate the high school system.

But they, like me, discovered that the skills that students were using to get them into college would not get them through college.

Many people — including faculty, parents, and administrators — are surprised when high-performing high school students struggle in college. But if we look more closely, we see the disconnect: our students were taught how to succeed as students, not how to thrive as learners.

You may think that operating as students and learners is merely a semantic difference. But it’s much deeper than that. Look at how transitions can befuddle professionals.

Professional Empathy: A Mirror for the Academic Experience

Many professionals and parents can’t appreciate the transition traps high school graduates face in college. If you struggle to empathize with students navigating this transition, consider the following professional scenario.

You’re a seasoned employee who has excelled in your role. Your evaluations are stellar, and your peers respect your work. You take a new position — similar responsibilities, but higher expectations. You respond by working harder and putting in more hours.

You’re confident when you submit your first big project. But your new supervisor is underwhelmed. In fact, she questions your effort.

Confused but committed, you ask for feedback. You follow her suggestions closely. Yet, your next project still falls short. This continues. No matter how much harder you work, the results don’t meet expectations.

Over time, you disconnect. You stop caring as much. You start focusing your energy elsewhere — family, hobbies, side projects. Eventually, you become the “average” employee your supervisor accused you of being.

Transitional Empathy: What Students Are Actually Going Through

That experience — the lack of clarity of assignment, the hopeful effort that leads nowhere and the inability to properly adjust — is what many students experience in college.

That experience — the lack of clarity of assignment, the hopeful effort that leads nowhere and the inability to properly adjust — is what many students experience in college.

😉They arrive believing they’re prepared. They work hard. But then comes that first test. The grade is low — much lower than expected. And when the teacher goes over the correct assessment responses, students report feeling like they “knew it.” They can’t believe they got it wrong then.😵💫

So, they adjust — study harder, longer, or use a new tactic for the next exam… only to fall short again.😡

This isn’t just a confidence issue. It’s a skills and perspective mismatch.

Students quickly enter what I call the Failure–Frustration Cycle — trying harder, getting the same disappointing results, and gradually disengaging. Not because they don’t care, but because their effort doesn’t yield results.

After hundreds of focus groups and years of working with colleges and universities across North America, I’ve seen the same pattern play out over and over again. In high school, students are taught to be good students — to show up, do their homework, follow instructions. But college requires something more. Something elusive and abstract, yet necessary.

In college, students must become great learners — individuals who know how to convert acts of studiousness into effective learning. That’s a different skill set.

Okay, back to your good students.

Great Things Happen When You Prioritize Your Good Students

If your goal is to build a culture of academic excellence, as many state in their strategic plans, then the math matters.

Too often, colleges invest heavily in the top 10% of students — through honors programs, scholarships, and advanced opportunities — and the bottom 10% — through tutoring, alerts, and support services. This leaves the middle 80% largely untouched.

That’s your leverage point.

When you reach the students who already care, but just need a new mental model, better tools and clearer guidance, you create institutional momentum. You shift norms. You raise expectations. And you improve outcomes across the board.

In my work during my early years with Lenoir-Rhyne University, for example, I focused on this exact population.

The results were dramatic:

- The nursing school hit a record performance in two years.

- The football team’s GPA rose from 2.1 to 3.2 in just one year.

- After three years, the student-athlete’s GPA surpassed the overall student GPA.

- After four years, faculty who once expressed that they despised teaching certain student-athletes were now presenting at conferences on the joy of teaching them.

- The school enjoyed more than a decade of unprecedented academic and athletic successes.

Rather than settling for a curriculum adjustment or professional development, focusing on good students created a cultural change, a realignment of relationships.

This wasn’t a one-off. I have seen other institutions make similar impressive gains by harnessing the power of this population.

🧾Check out some of the receipts from my work with Lenior-Rhyne and other schools: Receipts

Recent Good Student Project

Empowering good students still produces outstanding results!

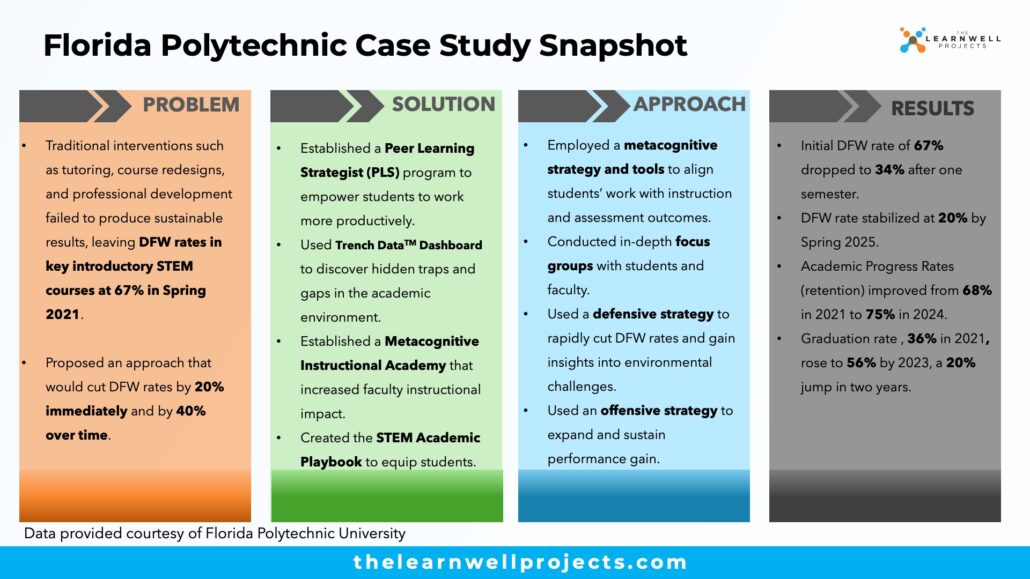

More recently, Florida Polytechnic decreased DFW rates by 47% using the same approach, leading to historic gains in retention and enrollment.

These outcomes aren’t anomalies. They are the result of a systematic focus on the right students — the good students.

Why Good Students are Overlooked

This conversation happens too often at far too many schools.

In a recent meeting with a group of institutional leaders, I posed a simple question:

Me: Have you identified your good students?

Leaders: (Puzzled) Not specifically.

Me: Do your faculty talk about your good students?

Leaders: Not really. The conversations tend to focus on the students who don’t show up or don’t turn in work.

Me: Okay — how many students typically don’t show up for class?

Leaders: Maybe one to three students per class, out of twenty.

Me: And how does the institution respond to those students?

Leaders: We have an “Alert” program. Then a committee or two meets, and we try to coordinate a triage of services — tutoring, advising, counseling — to support them.

Me: So just to clarify — you’re devoting an entire system of people, processes, and resources to support the two or three disengaged students?

(Silence.)

Me: What about the other 90% of students who do show up? What if you focused on helping those students produce higher-quality work?

Leaders: (Nodding) That actually makes a lot of sense. But we wouldn’t even know where to start.

My goal in these conversations isn’t to criticize — it’s to reveal the imbalance. When institutions invest the majority of their attention and resources into a small fraction of disengaged students, the return is marginal at best.

Once leaders recognize this misalignment, the conversation can shift. That’s when we begin exploring how to build a system that reaches the students who are already showing up — the good students — and empowers them to do higher-quality academic work.

That’s the path to real culture change. Not through triage, but through transformation.

Reflection for Institutional Leaders

Campus leaders. You can begin to recognize your good students by asking these questions.

Who do we talk about most in meetings — our top students, our struggling students, or our good students?

What programs, workshops, or resources are specifically designed for that “middle 80%”?

Are we rewarding effort, or are we building real learning capacity?

If you’re not sure how to answer, you’re not alone. Many institutions find themselves in the same position.

Hopefully, this article has nudged you to ask a different set of questions. Once you do, you will need tools and tactics to empower your community to elevate this population.

Here are five essential lessons and tools I’ve used to help transform good students into great learners — and institutions into thriving academic communities.

Lesson 1: Help Students Understand the Environmental Shift

Good students are transformed into great learners when they adjust to become independent learners.

Good students often enter college with a high school mindset: “Work hard, and you’ll succeed.” But college requires a shift from a dependent model of learning (teachers guiding every step) to an independent model of learning (students managing their own thinking and progress).

One student from a prestigious academy put it best:

“In my school, they didn’t teach us how to learn, they just taught us how not to be outworked by anyone.”

Another added:

“They taught us many concepts, but never how to learn concepts.”

Students notice the gap. They work harder, but their results plateau. They don’t need more effort — they need a strategic approach and new tools to enhance their thinking.

Use the following illustration and video clip to help students and educators make the proper shift in perspective and practices.

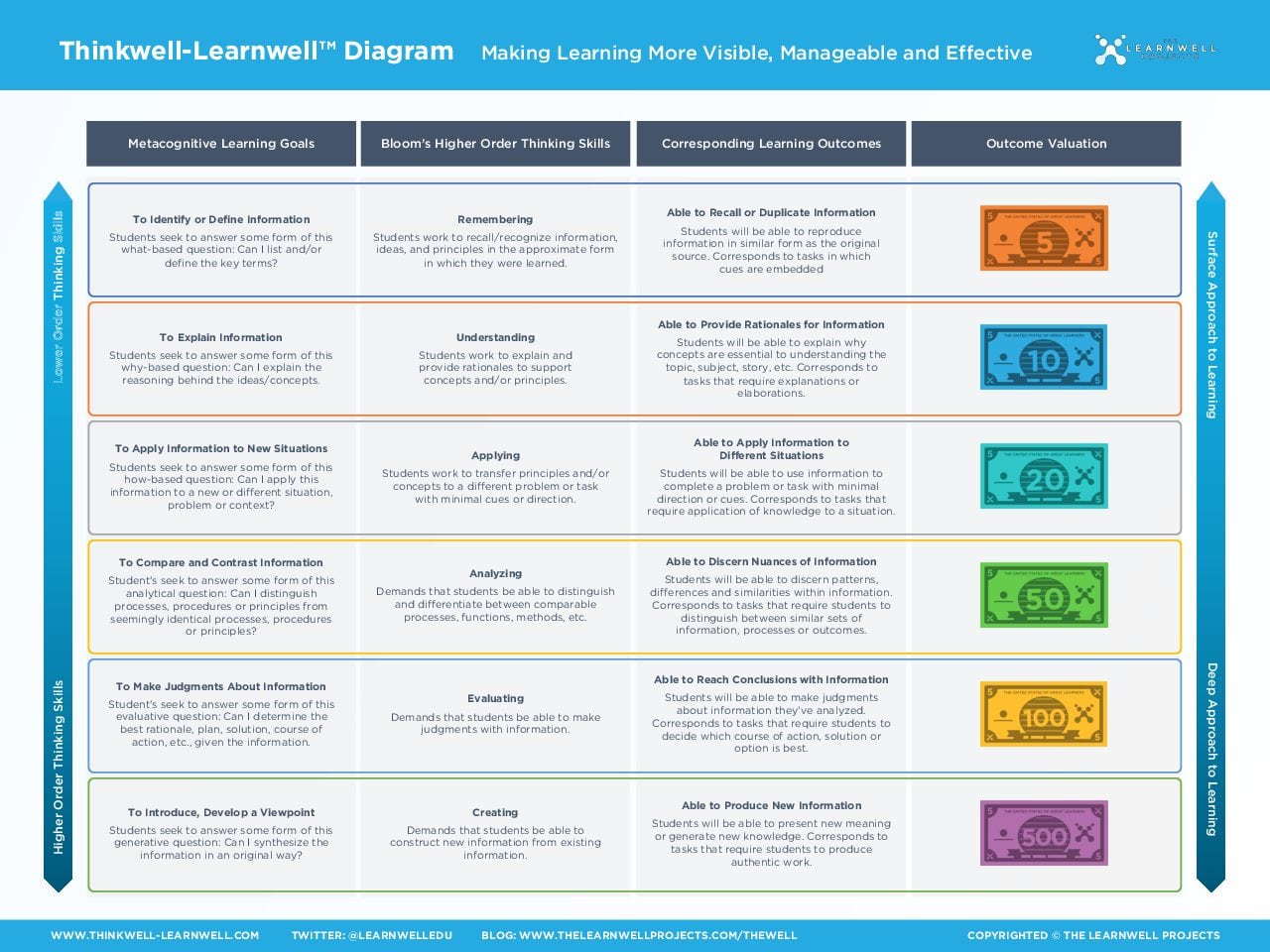

Lesson 2: Teach Students to Differentiate Thinking Skills

Good students are transformed into great learners when they can differentiate among thinking skills.

This is the most essentiat academic skill! Yet, it is the least possessed skill.

Most students — and many faculty — can’t articulate the qualitative differences between analyzing, applying, or evaluating. Yet these distinctions are foundational to academic success.

The ability to differentiate among cognitive skills is a threshold skill — a door students must walk through to do the kinds of cognitive complex tasks that are routine in college.

Once students learn how to recognize and apply different types of thinking, they begin to:

- Study with greater focus and purpose.

- Understand why some strategies work better in certain contexts.

- Engage with course material more meaningfully.

Faculty also report more effective instruction. It’s a win-win.

👉🏿GET YOUR FREE TOOL: Download the ThinkWell-LearnWell Diagram for FREE from my website at https://thelearnwellprojects.com/learnwell-tools/.

🔨Elevate your learning space with oversized posters of this tool: TOOLS.

👉🏿WATCH THIS TOOL IN ACTION! Use this animated explainer video from my YouTube playlist to teach faculty and students how to use the ThinkWell-LearnWell Diagram to differentiate among thinking skills.

Lesson 3: Help Students Decode Course Outcomes

Good students are transformed into great learners when they can decode their course outcomes.

This is the second most essential skill for academic work. It too is unknown by most educators and students. Yet, when faculty and students experience it in my workshops, they can’t believe they’ve been teaching and learning this long without it.

Once students understand thinking skills, the next step is decoding what their courses actually ask of them. This means breaking academic work into three key components:

- Content – What’s being taught?

- Cognition – What thinking does it require?

- Outcomes – What will students need to do with that content?

When students learn to decode course outcomes, they stop memorizing isolated facts and start making meaningful relationships with academic material.

I have an animated video for you that will make this skill plain and simple for you.

Lesson 4: Show Students How to Do Metacognitive Note Analysis

Good students who are transformed into great learners do metacognitive notes analysis.

Good students take notes. Great learners make notes.

This practice involves comparing the levels of thinking in their notes with the level of thinking required on assessments. When students learn this skill, they close the gap between studying hard and studying well.

They no longer view studying as “review,” but as cognitive alignment.

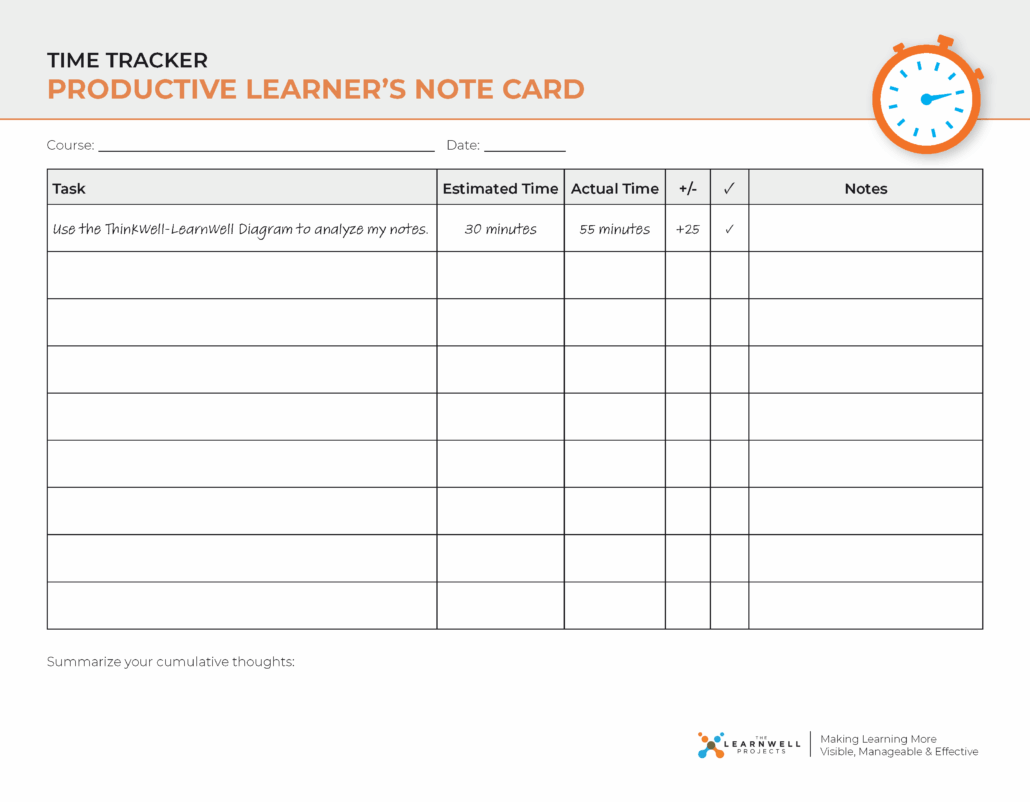

Lesson 5: Teach Students to Overcome The Real Time Management Challenge

Good students become great learners when they use metacognitive metrics to apportion their time.

Good students use the wrong metrics for academic tasks. They use measures such as effort – “I’ve studied so hard for this exam.” or time “I’ve studied X amount of hours for this class.”

If you’ve ever encountered students who feel rushed when studying or always run out of time, it’s likely because they are apportioning their time the wrong way.I

I created a Metacognitive Time Tracker tool that students and educators have used to develop better time apportionment skills. When students use this tool, the develop a clearer relationship between cognition and time, which benefits them in academic work and in their careers.

👉🏿WATCH THIS VIDEO! I created the following video to illustrate how you can teach students this powerful skill. (It may also help you as a professional or parent as well.)

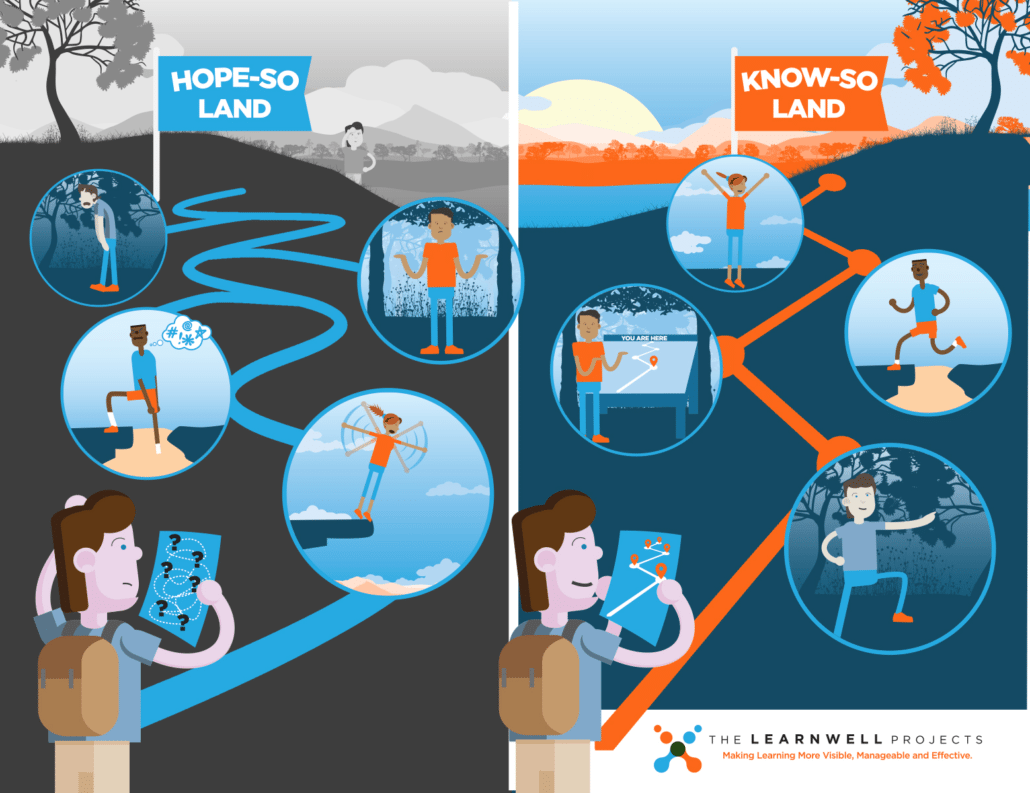

The Reward: Students Transition from Hope-So Land to Know-So Land

Good students often rely on hope:

“I studied hard — I hope it’s enough.”

But great learners don’t hope. They know. They know what the assignment demands, what kind of thinking it requires, and whether their preparation aligns.

Helping students move from Hope-So Land to Know-So Land is the ultimate goal. That shift is the difference between inconsistent performance and sustained academic success.

Good Students Are Your Greatest Asset

Here’s a surprising truth: Most institutions are still overlooking their greatest opportunity for academic transformation. It’s not at the top or bottom of the performance curve. It’s hiding in plain sight — in your good students.

If higher education is going to rise to the moment, we must stop overlooking our good students and instead help them become great learners. That’s the difference between students who get through college and those who grow through college.

We must expect more than developing harder working students. Instead, we must transform them into learners. The difference between the two states will decide on whether higher education’s has a bleak or bright future.

If we want our institutions to weather the enrollment cliff, navigate public scrutiny, and fulfill their mission, we must invest in the students who already want to succeed — and show them how to do it at a higher level.

Your good students are waiting. They’re raising their hands in class, coming to office hours, and doing what they’ve always done — but quietly wondering why it’s not enough.

Let’s help them turn effort into excellence.

Because when good students become great learners, everyone rises!

🤔COMMENTS ARE WELCOMED.

Check out the comments below for insights from students and educators.

Leave a thoughtful comment if you’d like a PDF version of this article.

120 comments

kurye

I admire your ability to tackle complex issues with clarity and compassion.

Leonard Geddes

Thanks Kurye. Your comments mean a lot to me because that is my core mission. Check out my forthcoming book at: http://www.transitiontraps.com.

Carla Hatfield

I will use this diagram to incorporate an acitivty about the differences in college and high school. This will really bring clarity to students about what college is and is NOT. I like how you utilized this diagram to show the connection of mutiple points of learning in high school and college.

Leonard Geddes

Thanks Carla,

It’s great to see that you are still doing impactful work!

Yusuf Aboudi

If only I was taught this before college. This was a amazing article it made me more woke and helped me open my eyes. I can definitely relate to this article.

Kevin

I really wish two things: (1) I had read this before spiraling into failing out of college with no foreseeable opportunity of returning (at least for several more years) and therefore halting any chance of success in getting my dream job; and (2) that far more educators would also read this and apply it, especially in STEM-based degrees where frankly the stereotype holds (in my experience) of a limited mindset in teaching and a focused mindset in being a nerd and not understanding how to teach nerd.

I’m saving this article and hope to find it when the future allows me an opportunity to return to college, and therefore hope to enter college post-40-years of age with no career prospects past 50.

Emily

Hi! I’m a current college student and I see myself falling into the traps mentioned in this article pretty often. However, can you clarify on the 20/80 rule in college? How should I go about in developing the 80% of knowledge that is not imparted?

Jenna

Hello! Thank you for taking the time to think about the overlooked “good students”. I think this article explains why I am doing so badly in college but it doesn’t really give instructions for what the next step is. I went from being an all-A student to struggling to pass my classes despite my efforts and studying which is so discouraging. While I can understand why all these things are happening I still don’t understand how to make any changes to fix these issues.

Leonard Geddes

Hi Emily-

You develop the other 80% by using your thinking skills to go beyond the content that was delivered in class. For example, let’s say your professor references a definition of evolution and a definition of natural selection. She may reference a couple of examples to add more life to the definitions. Your job is to recognize that this information is only a small portion of what she will expect you to know. I can’t tell you exactly what she will want you to know, but I can tell you that, if the course is challenging, then you will need to know the information at a deeper level than this. So, you might use the ThinkWell-LearnWell Diagram to analyze the difference between evolution and natural selection. If you do the work to extend your knowledge to this depth, then you will be able to answer question prompts that are asking you to perform at this level. This is the other 80%. I hope this helps.

Raj

These are immensely valuable tips and insights for any college student to maximize not just the college experience but also self esteem and performance.

Jon

Great article, what you wrote really resonated with me because I could relate to many of the conditioned biases of a pre-college learning environment. I will review the outlined tips regularly in order to get back on track with academic achievements.

Bethany

Wow this is definitely me… I’m a senior in college and I have never realized any of this until now… I feel ashamed for not knowing but no one ever told me..

Gaynor Groenewald

This is exactly what I need to understand why my child is having such a hard time adjusting!

Sandeep Sharma

I am a freshman in college and struggling with the same problem. I can’t be the student that I was in my high school. Now, after reading this article, I am figuring out the reasons behind it and also trying to solve all of them as soon as possible. This is well-researched article and helpful to students like me.

Joanne Chung

I totally agree with this method. I have been struggling to adjust to college and i think this will help me out.

Ningkang Zhao

I love this article, because it’s just reflect my situation right now. I really want to adjust myself and adapt the college life. I think this article will help me a lot about it.

Shuo Hu

Thank you for sharing!

I was confused by same question for many years. Luckily, I found the explanation and solution in your article. I am looking forward to my future, in other words, college life!

Alex

Great information so insightful and really enlightening.

C. Johnsone

I really like the 80/20, 20/80 approach to explaining the Teacher focused approach vs the Learner focused approach!

Alicia

Thank you for this information! my son is a college freshman and falls right into “good student” category. I’m sending him this information!

Kimberley Jensen

Interesting observations. I wonder how different math classes are from high school math classes. I don’t think that we require them to do much more than apply the information that they have learned.

Steph Bebensee

The 80/20 – 20/80 concept is exactly what students need to understand upon entering college. I think the way this concept is represented is clear and help frame one of the major academic challenges facing students. Very rarely is ability the root of poor academic achievement, the cause is most often related to one’s effort.

B. Lal

Is it ok for these “good children’ to misbehave in class? Is there a reason for this misbehavior by them ? This is in the high school context.

Carley

Very useful information–thank you!

Denise Gravitt

I struggle with getting students to understand that they need to put more effort into their studies in college than they might of had to do in high school, but could never explain it to their or my satisfaction as to WHY they needed to. I think this will help bridge the gap. May not convince them to do so, but if I can reach more students and help them to succeed that are currently struggling with how to do better I will be happy.

Julie Davis Good (formerly Turner)

Interesting approach to a conflicting group of data. As director of doctoral curriculum, I find significance in the “pipeline” discussion – why are we losing diversity of mind too early in the educational path. Your metacognitive approach reinforces those tactics we bring to our students! I look forward to additional discussions with my fellow faculty and administrators. Thank you.

Diane Flores-Kagan

I teach a Managing Writing Anxiety course. You talk about mindsets! I am looking forward to sharing the infographic with my students. Leonard has some of the best. Thank you!

Leonard Geddes

Diane,

Stay tuned for the forthcoming series on writing. I’ll cover the topic from the students and educators perspectives.

E. G. Lerner

I teach an honors section of a first year experience course at a highly diverse state university. This makes for a compelling classroom experience for me and my students. It also means that the students often arrive with widely dissimilar academic preparation. Your 80/20 approach offers a perspective that I feel will really penetrate and aligns well with my presentation of Bloom’s Taxonomy. Many thanks for a terrific article and the pdf!

Chris Baumbach

Great article! I would love to discuss this article with my College Success students this semester. I look forward to the PDF.

Sharon Jacas

When Good Students do Bad is a great article! Very informative and useful information. Can you please send me the link to the pdf of the infographic? Thanks

Minna

Thank you for sharing this article! And it connects to so many helpful resources. I am a Student Affairs professional who coordinates and trains Study Skills tutors, and this information reflects much of what we teach in our trainings, and in our workshops for students. It’s so useful to have this information brought together in one article, and linked to research. I’d love a copy of the pdf if you are willing to share!

Brook Masters

Love all this information and insight! Great conversation topics and visuals to introduce and discuss with Peer Tutors and SI Leaders, as well as in workshops with first year college students. Thank you!

K. E. Adkins

High schools bear some of the blame; by 10th grade high school students should be treated like they ARE in college. No more extra credit. No more getting points for making corrections on tests. No more acceptance of late assignments.

Leonard Geddes

I’m not sure if high school are to blame, but I do think the system in which high school operate bear some responsibility. My work with high schools show that teachers are responsive to a set of short-term metrics and outcomes that work for their environment, but are not compatible with higher education. I think federal and state legislative changes are needed to create a more seamless transition.

Heather Reed

Excellent depiction of the transition from high school to college!

Beverly Cribbs

We have begun talking reaching the “murky middle” of our students, and this article zones in directly on those students. This is a great resource as we are trying to better understand this group of students and develop programs and services to help them move to that next level of learning and success.

Jeanne Pettit

Using this information in a presentation for new student orientation today and tomorrow. Perfect timing! Will be reinforcing it in my UNV 101 course.

Leonard Geddes

These concepts have helped hundreds of students throughout the country and beyond make needed adjustments to college. Good luck!

Rivkah

I’m looking forward to incorporating these ideas into the first-year seminar I teach

Nancy McKinney

Many good points–I’ll share ” 80/20-20/80 ” with my students this first week of class.

Lynn

Interesting article. I look forward to looking closely at the infographic.

Heather P.

Very insightful article! I particularly appreciate the catch phrases to use when talking with students about building upon their strengths and shifting their paradigms. The 80/20; 20/80 mindset is hugely impactful! I really look forward to incorporating this information in campus stakeholder conversations and even training for academic peer leaders!

Michelle Gerdes

Very good article. I like the infographics.

Cheryl Wieseler

I see this every year as I advise new college students. The graphic will be a great illustration of the concept for them. Thanks.

Karen Sirum

Thanks for this concise and applicable description!

Kerry

Thank you for this perspective.

Dave Busse

I would really like to fold this into one of my introductory classes.

michelle Bufkin

Great article! I wonder if these same (or similar issues) occur in the transition from undergraduate to graduate school?

Cathy Tugmon

Very insightful article. I look forward to having a better look at the diagrams

CeCe Edwards

I am the director of my institution’s tutoring center, and this article struck a chord with me. These are the students who wait until after midterms to seek help because they falsely believe, “I’ve got this. I can do this.”

The transition of the great high school student to the “good” college student can also deal a heavy blow to her self-concept. In fact, many high school honors students I have worked with spend a good deal of time in denial that they could possibly be doing as poorly as they are in school. When the realization occurs that it is them and not the professor or the school, they are confused and sometimes devastated. They feel short-changed by their high school teachers and chagrined with college faculty and staff who didn’t emphasize the difference between high school and college enough. I understand why they leave.

Leonard Geddes

Well said! And this is why we lose so many good students.

Sue Mark-Sracic

The article is reflective of what I have observed as well at my university. Presenting the 80/20 principle and including the info graphic chart I believe would help students grasp what shifts in thinking might be needed in transitioning between high school and college.

TheRock

One hurdle for students is understanding that trying harder is not the same as trying better. Given that they’ve have invested those 20,000 hours in what may be unproductive behaviors, they need convincing and coaching in order to develop better habits of mind.

Leonard Geddes

The challenge is that students’ behaviors have been productive in their past academic environments. The best predictor of future behavior is past behavior, so it’s perfectly normal and expected for students to rely upon what has worked for them (hence the opening part of the article.)

Diane

Great information. Including the 80/20, 20/80 principle in a syllabus and reviewing these concepts the first day of class might help students know how to better apply their study time.

Leonard Geddes

I agree. It’s one of the most consequential concepts that students must learn, fully appreciate the implications and work out in their daily academic experience. In addition to teaching it the first day, I recommend you revisit it in subsequent weeks.

Lisa Crumit-Hancock

Thank you for your work and for creating this project to share and disseminate your concepts and ideas to your colleagues. I have been following and reading your posts for years and always appreciate your insight.

Leonard Geddes

Thanks for your interest. We have some awesome pieces coming out soon.

Jeff Weaver

Interesting article I will share with my first year college students this afternoon.

Lea

I’ve shared the original 80/20 rule with the parents of our incoming freshman at orientation. They appreciate having this information!

Doora

I have always wondered what has happen to me in collage! I was spending more time and getting less grades! suddenly the honor student was way behind. I felt so misplaced and since then I doubted myself and the major I have chosen!

I really wish I knew this beforehand!!