[et_pb_section admin_label=”section”]

[et_pb_row admin_label=”row”]

[et_pb_column type=”4_4″][et_pb_text admin_label=”Text”]

Earth is perfectly positioned within the solar system between Venus and Mars in a region called the habitable zone. This area is the only known territory where conditions are favorable for life. If Earth were to stray outside of this propitious zone, life would be impossible. Learning environments have a similar zone, a region where the teaching and learning experience is equally satisfying and rewarding for both students and educators. Unfortunately, few classrooms have the proper conditions in place to make meaningful learning more common. This article highlights some of the key points from a presentation series entitled Professors Are from Mars, Students Are from Venus: Learning Takes Place on Earth that I developed nearly a decade ago to help professors improve their classroom learning experience.

Like our solar system’s habitable zone, learning spaces must have certain characteristics that create conditions for optimal learning to occur. The teacher-student(s) relationship is central to this zone. This interaction is at the heart of every classroom. Students and professors often have vastly different views regarding the expectations and roles for each other in the teaching and learning relationship. Professors rarely recognize these differing viewpoints as the source of many of the seemingly intractable problems that have become endemic to academic classrooms. In truth, these distinctions undermine the educational experience. Professors and students both complain about each other in their own circles of influence. No surprise here! However, what may be less known is that both see the same problems. They simply interpret them differently. Students frequently complain that professors don’t appreciate how hard they work and that teachers try to trick them on assignments. Professors complain that students are apathetic and woefully under-skilled.

Coming from a counseling perspective, this experience is reminiscent of the situation therapists often encounter in clinical sessions when couples seek counseling to save or improve their relationship. Each person arrives with a stockpile of “evidence” that “proves” the other person is the problem. Each has a long formal list of injustices perpetrated by the other (and an even longer informal list of issues). The counseling relationship reveals, however, that the actual sources of their problems are not the behaviors that brought them to counseling; rather, they are unrecognized beliefs and assumptions, such as unspoken expectations, different perspectives on gender roles, and divergent value systems. Once these issues are exposed, couples may still fight, but they can at least tackle the real sources and are positioned to experience meaningful growth. Likewise, professors attribute frustrating experiences, such as students’ unwillingness to contribute to classroom conversations, students’ seeming inability to think complexly, and their continual request to know whether information presented in class is “going to be on the test” to student apathy and lack of skills. However, these issues are manifestations of a deeper unrecognized problem.

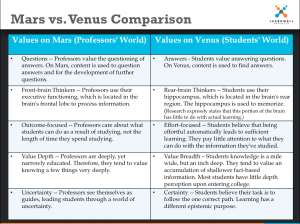

In the teaching and learning relationship, educators possess the power to create optimal learning zones. These are experiential spaces where conditions are ideal for meaningful and rewarding teaching and learning. College professors who accept that they operate on Mars and most importantly recognize that students have been raised on Venus are in a much better position to construct learning environments that are equally challenging and rewarding. The image rightward highlights some of the differences in values between residents of Mars and Venus. Given professors’ and students’ vastly different academic worldview, problems in the classroom are inevitable and predictable. Of course, educators who read this can easily conclude that new college students must realize that they are on Mars and change. However, I’d like to offer an opportunity to create an earth – a space where teaching and learning can occur. Below are three approaches that have been tried to some degree at my home institution and at other institutions in which I have provided professional development events.

In the teaching and learning relationship, educators possess the power to create optimal learning zones. These are experiential spaces where conditions are ideal for meaningful and rewarding teaching and learning. College professors who accept that they operate on Mars and most importantly recognize that students have been raised on Venus are in a much better position to construct learning environments that are equally challenging and rewarding. The image rightward highlights some of the differences in values between residents of Mars and Venus. Given professors’ and students’ vastly different academic worldview, problems in the classroom are inevitable and predictable. Of course, educators who read this can easily conclude that new college students must realize that they are on Mars and change. However, I’d like to offer an opportunity to create an earth – a space where teaching and learning can occur. Below are three approaches that have been tried to some degree at my home institution and at other institutions in which I have provided professional development events.

Fend for Yourselves Approach — This approach ignores or minimizes the differences that accompany students from Venus. Educators make little effort to help students adjust to the rigors of college academics. Professors bear no responsibility for students’ lack of success. In fact, colleagues negatively characterize their peers who develop strategies that help students succeed. This is often a default position and does not promote broad student academic success. Furthermore, it is an unrewarding teaching environment for instructors.

Scaffolding Approach — Within this perspective, academic programs, schools, colleges or entire institutions recognize and even embrace the place from which students are coming, and gradually and intentionally ratchet up rigor as students progress through the curriculum. The key challenge with this approach is to avoid instilling a false sense of intellectual security within students. Students who are successful on less rigorous assignments and assessment early on in the curriculum may become overconfident and will wrongly conclude that their study routine will sustain them throughout their college career. The key to avoiding overconfidence is to continuously and explicitly communicate to students that they are involved in a scaffolded approach to academic content. Students also must know when the rigor will be/has been increased, the types of outcomes the new rigor standards require and training as to how to adapt their studying to meet the new standards.

Dive into the Deep Approach — This is where students are immediately immersed in deep content and a heavy workload. For this approach to work, professors must be unified. If students encounter courses that are “easy” or memory-based and others that demand deep thinking and a heavy workload, they will likely develop negative perceptions about the professors who teach deeply.

I was a member of a team of educators who converted Lenoir-Rhyne University’s one-semester, one-credit hour freshmen transitions class into a two-semester, six-credit hour course. The previous “fluff” class focused solely on college knowledge stuff. The new course that we instituted about four years ago is reading, writing and research intensive. (It also includes college knowledge information and activities.) Building upon experiences that we recognized over the span of many years, the program designers envisioned that the course would provide first-year students the cognitive and behavioral competencies that would sustain them throughout their college career. While we are still working to perfect the course, we have made significant strides. Two years after its installation, faculty — many of whom were not part of the redesign or knew much about it — reported that students were demonstrating better academic abilities than their predecessors. National survey data later affirmed these anecdotal observations. We recently completed focus groups with students to capture their interpretation of the impact of the FYE course, among other things. While the data hasn’t been finalized, it seems evident that the FYE course’s Dive into the Deep Approach is playing a significant role in positioning students for success in college. Many students attribute their success in upper-level courses directly to their experiences in the FYE course. Perhaps, we are creating our own Earth! By inventing a system to push students forward in their academic abilities, faculty and students are beginning to praise the course in their circles of influence rather than complain. It’s a strange feeling!

Next week’s article: How Educators Can Get Awesome Class Evaluations from Students (even Struggling Students) in Rigorous Courses and Programs. Join the blog to ensure that you don’t miss this and other timely articles.

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column]

[/et_pb_row]

[/et_pb_section]

2 comments

Lois

Thank you, Leonard! Since I provide academic support to college students, I see immediate application to my work. The comparison chart provides a starting point for helping students understand why there is a disconnect between them and their professors. Once the differences are understood, they can then more effectively work at submitting the kind of assignments that their professors are seeking. Of course, I believe the professors need to understand students as well and make the effort to bridge the gap.

leonard.geddes@lr.edu

Thanks Lois! I realized long ago that all other relationships (e.g. personal, business, teams, etc) that getting faculty and students to “play from the same sheet of music” is perhaps the most important contribution I can make. This alone solves many of the problems. Please let me know how it “plays” with students and faculty on your campus. I hope you had a great year!